The Precedents Brazil’s AI Bill Could Set

An interview with Luis Enrique Urtubey De Césaris

I wanted to take a broad look at a piece of legislation in Brazil that—if passed—could carry significant weight with developers and serve as a template for other countries shaping their AI laws. Before my interviewee breaks it down, let me explain why we’re zooming in on Brazil.

Brazil has:

● The world’s 10th highest GDP & largest economy in Latin America

● 180+ data centers—more than any other country in Latin America

● Clean energy infrastructure that appeals to tech companies

● Third-biggest ChatGPT user base, after India and the U.S.

● Fifth-largest internet user base globally

Basically: Brazil is BIG in every possible way. A country with such a huge user base and economy, along with its potential to become Latin America’s data center capital, is very likely to have a significant influence on how AI is shaped.

To explore this, I spoke to Luis Enrique Urtubey De Césaris, who has spent the past year working with policymakers, civil society, and other stakeholders regarding several AI governance initiatives in Brazil. He directs the newly founded Centro de Estudos em Governança de Inteligência Artificial, serves as an AI expert for the Observatory for Catastrophic Global Risks and has spent the last decade as a technology-focused super-forecaster* at Good Judgment.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. Interviewer: Meenakshi Dalal (MD) Interviewee: Luis Enrique Urtubey De Césaris (LEU)

Brazil’s AI Bill and Why It Matters Now—Even If You Don’t Live in (or Anywhere Near) Brazil

MD: Can you explain briefly what this bill is?

LEU: Bill 2338 is the main piece of AI legislation currently under debate in Brazil. It establishes a framework to govern AI in the country, designed to mitigate AI risks of every kind.

The bill classifies AI systems by risk level, creates a national governance structure for oversight, and grants regulators several powers to try to guide the development of the technology in a positive direction. It’s also further along in the legislative process than almost any of the other 120+ AI-related bills in the country.

It is important to underscore that the bill is under very active debate and, in case of becoming a law, the specific final wording and ensuing regulatory process is likely to be of great importance.

MD: What does it apply to?

LEU: If it comes into force, it would apply—in a way or another—to all AI systems available for commercial, economic, or public use. Eventually, other laws would be expected to cover other potential uses.

MD: And how close is Bill 2338 to becoming a law?

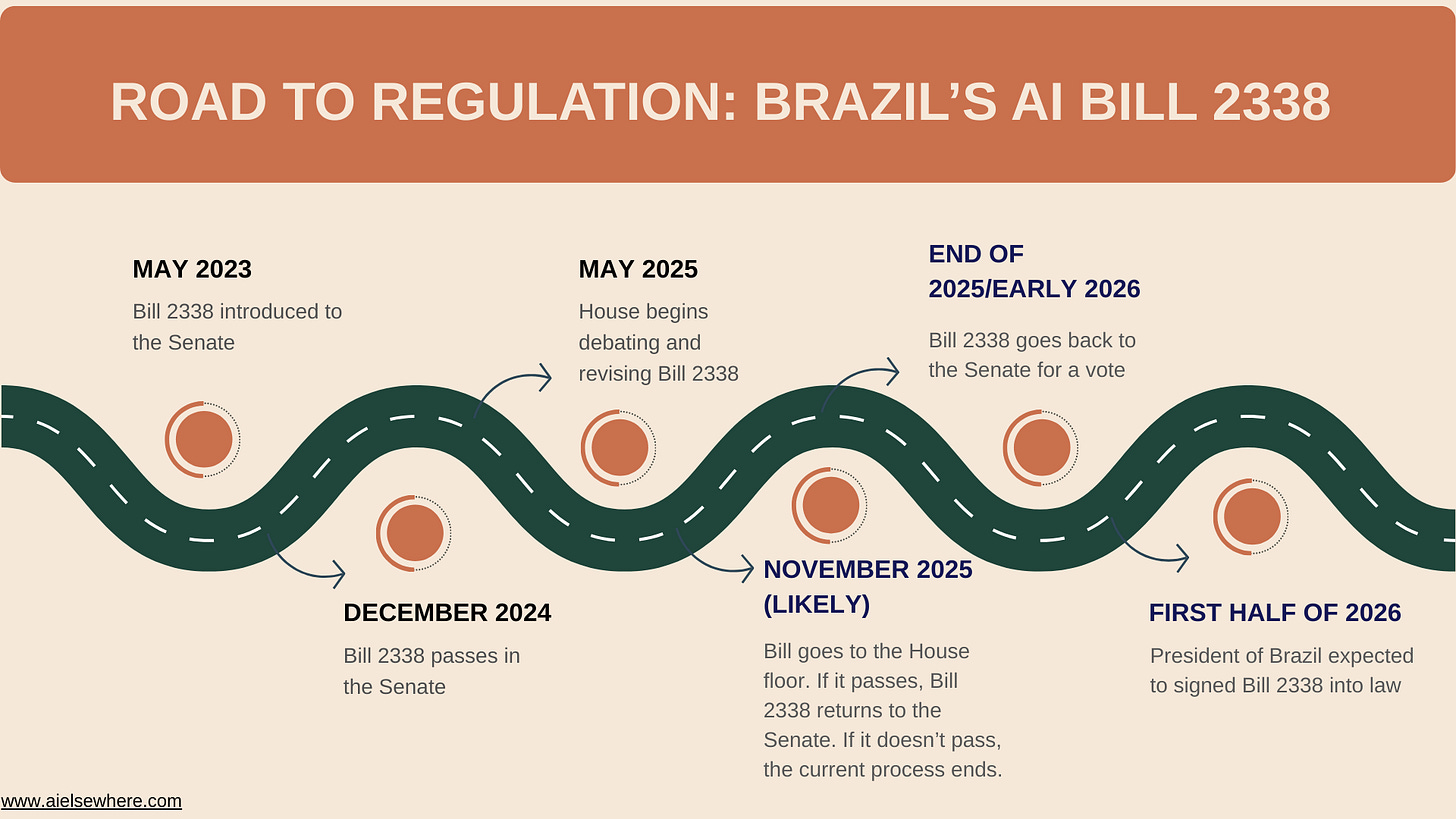

LEU: It’s about halfway there. The bill was introduced to the Senate in 2023. An amended version passed there in December 2024 and moved to the House for debate in 2025. A newly amended version is expected to go to a House floor vote at the end of 2025.

If it passes, the bill returns to the Senate for a final vote before landing on the president’s desk. Everything else being equal, it’d likely be signed into law in the first half of 2026.

Some articles of the law would enter into force as soon as it’s signed into law, but most provisions would only go into effect six months to two years afterward.

A Roadmap of the Legislative Process for Bill 2338 to Become a Law in Brazil

MD: The number of pieces of AI legislation floating around the world is overwhelming. Why does this bill matter so much both in Brazil and for people and companies nowhere near the country?

LEU: Several actors intend for Brazil’s AI policy to serve as an example for the rest of the world, particularly among countries in the Global South. This goal is explicitly stated in the country’s National AI Plan (the other main AI policy document at present), which is more focused on the development of the technology as such.

It would be analogous to the so-called Brussels Effect,* in which other countries and regions take up, or are inspired by, the standards set in other jurisdictions.

MD: And is it correct to say that Bill 2338 is an example of the Brussels Effect in action?

LEU: Yes, to some extent. The easiest, shorthand way to understand this bill is to know that it is inspired by the European Union's AI Act, but with evolving local differences.

How Brazil’s Bill and the EU’s AI Act Compare

MD: Can you walk me through how Bill 2338 is similar to the EU AI Act?

LEU: In broad terms, Bill 2338 takes core elements from the EU AI Act to address similar concerns. It takes a preventive, harm-reduction approach grounded in transparency and fundamental rights.

Like the EU’s law, it follows what we call a ‘risk-based’ approach. It lays out an AI system’s possible uses and categorizes them as posing an excessive risk, high risk, or other. Each classification carries a set of obligations. For example, a ‘high-risk’ AI system—like self-driving cars—would have to undergo a preliminary risk assessment before it would be allowed in Brazil.

Brazil’s proposed law—like the EU AI Act—also covers systemic risks* from General-Purpose AI* models.

It also sets up a framework for serious incident reporting, establishes some whistleblower protections, and the possibility of third-party audits. The bill creates a national AI governance system, coordinated across agencies and ministries, that would oversee and enforce regulations. In the most extreme case, if a model is deemed too dangerous, it could be banned outright. This would most likely occur if other preliminary measures didn’t reduce risks satisfactorily.

Bill 2338 takes core elements from the EU AI Act to address similar concerns. It takes a preventive, harm-reduction approach grounded in transparency and fundamental rights.

—Luis Enrique Urtubey De Césaris

MD: What are the main differences between Brazil’s proposed bill and the EU AI Act?

LEU: While using some central principles from the EU AI Act, lawmakers are also adapting them to local conditions, particularly in how the AI governance system would be structured. The European Union has its own version, with an office at the European level supported by national agencies.

In Brazil, it is a national system designed in a way which also mixes elements of both centralized and decentralized governance, looking to adapt to the needs of each sector, industry, or application. In this sense, they’re trying to make this law as future-proof as possible.

At present, the Brazilian legislature is in the process of trying to strike a more explicit balance between innovation and regulation, compared to previous drafts, showing that both can operate without being at odds with each other.

This is not a straightforward process. A lot of this approach comes from recent public-administration theories and practices—what could be called experimentalist governance.* It’s in part also a political process, so how much of this survives once the rubber hits the road is to be seen.

There are differences around exactly how systems would be regulated and to what extent. For example, the EU’s law has four risk levels, while Brazil’s has three. Also, while both pieces of legislation cover systemic risk, the EU’s definition of systemic risk is more precise than Brazil’s and links to AI systems’ potential to cause catastrophic harm more explicitly. It also addresses AI model size as a key variable, which Brazil’s bill currently does not.

In Flux

MD: Okay, so there are quite a few differences between the EU’s AI Act and Bill 2338. Are any of those differences part of the current debate?

LEU: Yes, they are. For example, definitions are central to ongoing discussions, and we’re looking towards more specificity. Lawmakers are debating which AI uses belong in each category and the processes for updating them.

MD: Why are these important?

LEU: These definitions matter because they determine which AI systems would be regulated and how. If these aren’t clear enough, it may make enforcement difficult later on, as well as creating unnecessary uncertainty.

MD: What else is in flux?

LEU: For example, copyright protection is included in the bill right now, but the extent of those protections is under debate. The final form the governance system will take is an open issue.

MD: I read that the Minister of Finance is courting tech companies to build more data centers in Brazil. From what I understand, this would come through a not-yet-public National Data Center policy that offers both tax incentives and access to Brazil’s renewable energy infrastructure. Does that affect the bill?

LEU: It might, directly or indirectly. The desire to regulate and develop local industry could be in some tension, depending on how it is structured. But we won’t know until the Ministry of Finance publishes the proposed policy, likely sometime in September. It is expected to be focused, in part, on tax exemptions for the data center industry.

Concern and Optimism

MD: During the past year, you’ve talked at length to many people who have an interest in how this bill turns out. What’s one thing you would say people are particularly concerned about?

LEU: Especially when it comes to small and mid-sized companies, there’s concern about having the right responsibilities and obligations assigned to appropriate actors, while simultaneously allowing for the development and deployment of the technology. For example, upstream* and downstream developers* would need clear definitions about what each could do.

People are optimistic that this bill and other policies could make Brazil a global leader in the development, deployment and governance of AI. —Luis Enrique Urtubey De Césaris

MD: What are people optimistic about?

LEU: People are optimistic that this bill and other policies could make Brazil a global leader in the development, deployment and governance of AI.

There’s also excitement when it comes to potential in the public sector: Brazil could create both a robust process of training government staff on AI and enable innovation more broadly. Regulatory sandboxes* could play a role in this.

The primary thing the bill does is try to create the conditions for different stakeholders to engage productively in regulation, and therefore hopefully shape the trajectory of the technology in a way which may serve the public interest.

Very concretely, there’s also optimism that this bill might lead to the prevention of crime and other types of misuse, such as stopping scams caused by AI deepfakes—something that has become a major issue both in Brazil and around the world. The thought is that if successful in reducing harm, Brazil would be a leading jurisdiction developing these regulations and contributing to an emerging global effort.

MD: As a proponent of ethical and safe AI, do you want this bill to pass?

LEU: Yes, I do. The bill is directionally good enough to be a strong starting point, and I expect that adjustments will be made between now and a final vote which will make the bill stronger.

In its current language, the bill gives regulatory bodies the flexibility to adapt the fine print as risks evolve, within a governance system which tries to be accountable and responsive. The bill opens the possibility of mitigating a broad spectrum of negative outcomes, including the most negative. And that’s a good thing.

My Two Cents: The choices Brazil makes in how it balances AI regulation, innovation, and investment will have ripple effects, especially if other countries follow its example. If Brazil offers AI developers leeway that the EU doesn’t, it could result in developers producing different versions of their models, one to meet the EU’s requirements and another to meet those of Brazil and countries adopting similar regulations.

Brussels Effect—When other countries adopt regulations modeled on the European Union’s standards.

Downstream developers—People or organizations that take a general-purpose AI model and customize it for a particular use, like healthcare or education.

Experimentalist Governance—A flexible, trial-and-error approach to policymaking that adjusts as new evidence emerges.

General Purpose AI (GPAI)—An AI system that can perform many different tasks, instead of just one. The same model might be used for image or speech recognition, generating audio or video, detecting patterns, answering questions, or translation.

Super-forecaster—Someone who consistently makes unusually accurate predictions about future events.

Systemic Risk—Large-scale threats that can affect entire societies or economies.

Upstream developers—People or organizations that build the original, general-purpose AI models before anyone adapts them for specific uses.

Subject: Story idea — Alignment before meaning in LLMs (structural, not values)

Hi Billy,

I’m sharing a short story idea that frames LLM alignment failures as a structural problem, not primarily a values/dataset issue.

Many failures (hallucination, inconsistency, misalignment) appear before meaning stabilizes — when the model’s perception locks into fixed “identity forms” (self/other/intent/agent).

I’m developing a framework called NCAF (Non-Conceptual Alignment Framework) with a companion method PMD (Perceptual Model Decomposition). Core claim: alignment must happen *before meaning*, at the level of perceptual structure.

If this is interesting, I can share a 1–2 page summary with diagrams + examples.

My post: https://northstarai.substack.com

Best,

Lee Chungsam